* Pantaenius UK Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (Authorised No.308688)

If a crewmember is seriously injured, the mast breaks or the vessel is taking on water; sometimes even the most experienced sailors fail to react prudently and with the necessary speed. But these kind of stressful situations can be rehearsed and the course of action practised, with the help of checklists and emergency rolls. This ‘dry training’ can be invaluable when things get serious.

The majority of sailors like to ignore the idea of an emergency at sea. Now that the boats are standing high and dry in winter storage, it’s the perfect time to think about strategies for dealing with various emergencies from the warmth of your living room. The yacht insurance specialists at Pantaenius offer various schemes and advice on emergency roles, which you can obtain free of charge from their boat show stands or your local office.

Read, talk and practice, ideally, with the full crew. Dirk Hilcken of Pantaenius explains why: "If a dangerous situation occurs on board, we automatically switch into a kind of survival mode. In concrete terms, this means that the body is set for rapid escape - a legacy from a time when we humans had to be on our guard against sabre-toothed tigers and mammoths.

“To proceed calmly when things get serious, this reaction is not particularly conducive, so we have to outsmart our brains. The more often we perform an activity, the less we have to think about the individual processes and the more it becomes second nature," says Hilcken.

As an example, he cites driving a car, in which we brake, clutch, shift gears and accelerate, without much brain capacity being tied up. It will certainly not be possible to achieve such a high degree of self-evidence as when driving a car when practicing emergency situations - but it is enough to remember the most important cornerstones and to do the right thing with the help of checklists or emergency roles.

Waterproof laminated checklists, adapted to the needs of ship and crew, as well as a list of the various emergency castors, should therefore be available on every ship - either visibly attached to the bulkhead, the chart table, or in an easily accessible ‘emergency drawer’. This should also include a plan of the boat on which, for example, all sea valves or all places where water could penetrate into the ship are marked.

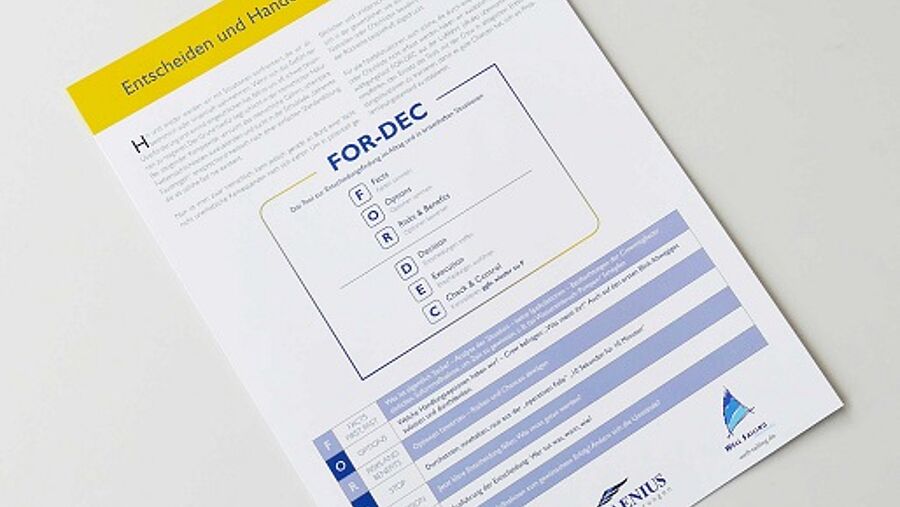

"In 90 per cent of cases, water enters a ship through existing structures," reports Hilcken. "If a water ingress is detected, you can systematically check all possible entrance points, from sea valves to coker, without forgetting any.” In addition to checklists and emergency roles, Pantaenius recommends integrating the crisis management tool "FOR-DEC" into safety planning. FOR-DEC originates from aviation and is also used in commercial shipping.

It represents a decision-making scheme with the stages "Facts" (F) - "Options" (O) - "Risks and Benefits" (R) - Stop (-) - "Decisions" (D) - "Execution"(E) - "Check and Control" (C). Pantaenius recommends training the use of the tool with the crew in everyday decision-making situations so that it has a good chance of establishing itself as a problem-solving standard and strategy.

So use this chance to sit down and summarise the most important steps in an emergency on a ‘cheat sheet’.